Citizens have freedom of speech and of the press in keeping with the objectives of socialist society. Material conditions for the exercise of that right are provided by the fact that the press, radio, television, movies and other organs of the mass media are State or social property and can never be private property. This assures their use at the exclusive service of the working people and in the interest of society.

The law regulates the exercise of these freedoms.

The story is still somewhat confused and incomplete, partly thanks to the lack of a free and reliable press in Cuba, but some time around Sunday July 11th in Cuba’s San Antonio de los Baños, protests broke out against the country’s worsening economic situation and bungled handling of the COVID pandemic. To screams of ‘we want vaccines’ and ‘down with the dictatorship’, Cubans marched in an unprecedentedly anti-government and open fashion. Protests soon spread to major cities like Havana and Santiago de Cuba in the span of a day and continue even now. The uploaded Facebook video (which was soon yanked, but not before being uploaded to YouTube by dissident media 14ymedio) shows hundreds of Cubans protesting in the streets:

In a police state like Cuba’s, maintained by a sclerotic communist apparatus, that’s already news enough. What’s even more unprecedented is that news of all this turmoil, complete with tweets and livestreamed video, has started to leak out of a country whose internet adoption has been one of the slowest in the world. There’s a fascinating hashtag duel between #PatriaOMuerte (“fatherland or death”, one of the revolution’s many tag lines) and #PatriaYVida (“fatherland and life”), each piling up their respective threads.

In order to understand why it is that the world gets to see, unfiltered by either Cuban or Western media, the reality of this isolated island nation, you need to understand the strange and utterly mangled state of Cuban internet.

This right here is the scene in just about every public square in Havana:

Cuba has no internet, at least not how you understand it.

Cellphones were illegal in Cuba until 2008; an American named Alan Gross who gave out a few to Cuban non-profits was sentenced to 15 years in 2011 for such heinous behavior (he served three, sprung in a 2014 prisoner swap with the US).

Since their legalization, smartphones and internet are nominally allowed, but functionally limited due to limited access and (by Cuban standards) stratospheric pricing. How a Cuban typically accesses internet is via weak and overloaded Wifi in one of a limited number of public squares, everyone sitting around and crowding by the one antenna while checking email or videocalling relatives in Miami. The nominal cost for an hour of internet in 2017, when I was there and buying the little scratch-off passes like everyone else, was $4. When you consider the real-money Cuban wage—Cubans get paid in worthless non-convertible currency, but the government charges tourists and foreign companies in hard currency—is something in the $20-$30 range, you can see how the internet is severely limited in practice.

Stop for a moment and ponder the impact of streaming video on your well-connected life: every bodycam video you’ve ever seen, every online blowup over what someone did in real life, that whole piping of the world’s eyeballs into that black mirror in your pocket (and yours into the world’s pocket): Cuba has utterly and completely missed that memo until now.

As with everything else in their severely constrained lives, Cuban have figured out means to ‘resolver’ (Cuban slang for various forms of lifehacking, either legal or not).

“El paquete” (the package) is a several terabyte compendium of (no shit) a week’s worth of internet on a hard drive. How your average Cuban interacts with the internet is buying a ‘paquete’ (for something around a dollar), having it copied to a USB stick or hard drive, and then browsing it offline on whatever rickety laptop or computer they have at home.

All those ‘paquetes’ are copied in one central Havana location, and then physically smuggled to all the cities in the provinces. For the geeks reading, yes, Cubans have built one of the biggest ‘sneakernets’ on the planet, out of sheer necessity alone. For most Cubans, the ‘internet’ is still physical media you carry around.

It gets better: Cubans also built one of the biggest ad hoc wireless networks in the world. ‘SNET’ was a wide-area mesh network built out of repurposed wireless equipment by gamers who wanted to play networked games like Call of Duty, but which soon morphed into an internal clone of the outside internet. Knockoff versions of Instagram, Facebook, etc. all sprung up, outside the control of the government. Nothing that free can last in Cuba; in 2019 the government shut the network down, supposedly to eliminate competition with its new cellular data service, or simply to enforce Article 53 of the Cuban constitution (quoted above).

(For a longer exploration of how Cubans manage to get online, read my 2017 WIRED piece where I managed to get inside the ‘paquete’ network, SNET, as well as the tiny but burgeoning Cuban startup scene.)

Starting in 2018 cellular networks were finally available to average citizens, but still prohibitively expensive and also terribly slow. Still, this was a momentous step.

Stop for a moment and ponder the impact of streaming video on your well-connected life: every bodycam video you’ve ever seen, every online blowup over what someone did in real life, that whole piping of he world’s eyeballs into that black mirror in your pocket (and yours into the world’s pocket): Cuba has utterly and completely missed that memo until now. It was simply a technology that didn’t functionally exist, and now, while the government keeps the internet on at least, it does.

There would have been no Arab Spring without Twitter and Facebook, no freakout about the Covington School kids, and no George Floyd and no BLM without that video; the wars that matter now are the ones that happen inside The Spectacle, the parade of images that refract our reality. Cuba, that Communist dinosaur, has never been subjected to any of this.

Consider this video, for example, particularly the closing seconds where government thugs grapple a protestor into a car, and everyone shouts ‘Libertad!’:

Cuba has no freedom of assembly in practice, and constitutionally has no freedom of speech by private citizens. And yet here we are in a scene that looks straight out any of the countless social-media video blowups that now punctuate our lives online, from the Kavanaugh trial to some act of police brutality. We’ve been inured by it; it’s just part of our daily grind now, though it still manages to keep us all on the rage and dopamine rollercoaster. That line of hands holding up phones, that phalanx of accountability that we’re accustomed to seeing as the front-row seat to, well, everything…that has never really been seen in Cuba at scale.

To watch that media script play out in Cuba is simply astonishing. There’s no telling where this goes. If you believe (as I do), that mediating reality through ubiquitous and decentralized networked screens has rocked human life to its core, I don’t see how this doesn’t shake up something in Cuban society.

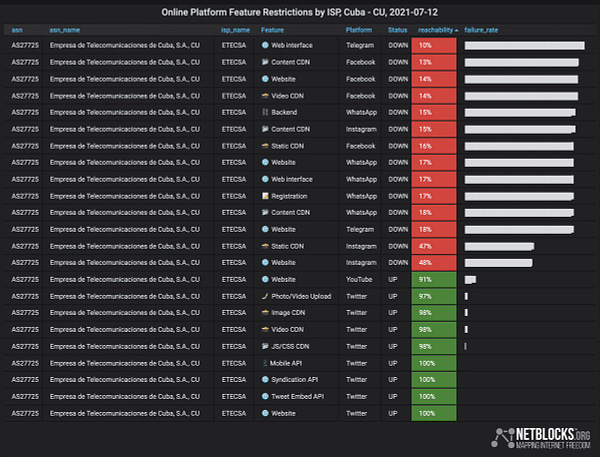

Assuming of course the internet actually stays up. The government has an absolute monopoly on all internet and media and routinely blocks certain sites or services. According to the Netblocks internet observatory, as of today Monday July 12th, Cuban ISP ETECSA is blocking all Facebook, Instagram, and Telegram:

While information can get out various ways, from VPN or satellite internet or even smuggled storage drives, for the flywheel of social media to really kick in, Cubans themselves need to engage with that flammable cocktail of real-life protesting and social media. The government is already stepping in to make sure they don’t.

I’ve spent the last two nights on a Twitter Spaces hosted by @GeekCubano and attended by numerous Cubans commiserating about that day’s mayhem and arrests in the protests. Most of the time, a speaker would be invited up only to have their connection cut or go spotty. Still, being at the cutting edge of social audio with residents of a country that’s still difficult to call via a landline is astonishing.

I later conferred with one of the veterans from the underground SNET network mentioned above (whose name I’ll obviously omit), who was trying to game the filtering the government imposed. The rumor was the filtering software was Chinese in origin, and would selectively kill social media connections or connections to VPN servers. My source was trying to use a combination of privacy-preserving VPN and Tor to reach the outside world. Ultimately however, the government controls all internet via monopoly, and can simply turn off internet since its backwards economy doesn’t critically depend on it.

The Cuban government’s reaction

The current Cuban head of government Miguel Díaz-Canel immediately broadcast a speech calling for the revolutionaries to take back the streets. In another address he even blamed Mia Khalifa(!) for helping foment the internal protests (Khalifa herself retorted with a vulgar Cuban characterization of the president). Just like that Cuba is being dragged into our social-media mud pit where elected officials trade insults with blue-check influencers.

The reality inside Cuba though is very much not the virtualized LARP of our political process. There, matters are still stuck in more Soviet-era realities.

In Cuba, the machinery of repression has been fine-tuned to an art. The days of a political gulag numbering thousands of prisoners or dissidents getting executed en masse following show trials, as was the case shortly after the revolution, is gone. Nowadays, the first stages of the state squeezing you are relatively soft acts of repression like arresting you while doing an interview with Western media (as happened to YouTuber Dina Stars) and disappearing you for a few hours or days.

Then come the actos de repudio (‘acts of repudiation’), whereby the local members of the Comités de Defensa de la Revolución gather outside your house screaming slogans and throwing rocks is the first stage in the state’s squeezing of you. Then follow harsher steps of ostracism against you or your family, until just about everyone caves.

If you actually organize and protest, the fate that awaits you is that of the human-rights group such ‘Damas en Blanco’ or independent bloggers like Yoani Sanchez: you’ll get roughed up or beaten, hauled away in a car and given a spell in jail. The jailings and beatings continue until you fold or flee. If you really refuse to surrender, you’ll die in a mysterious car accident as noted dissident Oscar Payá did in 2012. The video below, taken during Sunday’s protest, is typical (though our seeing them is certainly is not):

If the usual machinery of oppression fails and the protests continue, even if fully livestreamed to the West, then what?

Violent Tiananmen-style repression such as soldiers firing live rounds at massed civilians is something the Cuban government has never ventured to do, mostly because it hasn’t had to. Instead, the government uses flight to Miami as the escape valve for internal dissent, cracking open the exile pipe when things get really hot.

In 1980, when a group of Cubans drove a city bus through the gates of the Peruvian embassy and demanded political asylum (soon to be followed by thousands of Cubans), it spurred a diplomatic crisis that ended with Castro giving a speech1 at the port of Mariel announcing an open-door policy with the United States. That rhetorical flourish led to an unplanned small-boat evacuation similar to the one at Dunkirk, but led by Cuban Americans speeding across the Florida Straits with any boat that would do, and eventually boatlifting 125,000 Cubans to the United States (forming an entire ‘Marielito’ exile generation, depicted somewhat spectacularly in De Palma’s film Scarface).

In 1994, when a sputtering post-Soviet Cuban economy kept the Cuban population in even more misery than usual, spontaneous protests at Havana’s spectacular Malecón (the so-called ‘Maleconazo’) led to another implicit opening of the gates, and the Cuban Rafter Crisis was the result. It might surprise some younger readers to know that Guantanamo was first used as a holding facility, not for post-9/11 War on Terror prisoners, but for Cuban rafters (my former brother-in-law among them), who were sent *back* to a US base in Cuba before being (eventually) allowed entry into the US.

That line of hands holding up phones, that phalanx of accountability that we’re accustomed to seeing as the front-row seat to everything, has never really been seen in Cuba at scale. There’s no telling where this goes. If you believe (as I do), that mediating reality through ubiquitous and decentralized mobile computing has rocked human life to its core, I don’t see how this doesn’t shake up something in Cuban society.

If protests continue to grow in Cuba, I’d wager the government again opens the exile escape valve to calm things down. Truly iron-fisted repression involving dozens or hundreds of deaths is not something the current dictatorial regime would consider, and certainly not with dozens of smartphones looking on for the first time. One problem is that, unlike the other two times this stratagem was used, US immigration policy is no longer open to Cuban political asylum seekers. As part of Obama’s ‘opening’ to the island, he canceled US policy that granted residence to Cubans who managed to step foot on US soil. If the Cuban government opens the floodgates on their side, impatient Miami Cubans aren’t going to sit on their hands while their families fester on the island: Key West is only 90 nautical miles or so from Havana after all, a short ride on a fast boat.

In that scenario, the Biden administration will have a crisis on his hands as the Carter administration did during the Mariel boat lift. Given the tragedy of the Cuban revolution, and how every generation has had to make their way out of the country somehow, either as unaccompanied children (like my parents) or rafters risking their lives on the high seas, this would be a tragic but unsurprising outcome.

Thus far, Biden has messaged support for the Cuban protests; what he really needs to do is facilitate Cubans’ ability to communicate with the outside world via whatever technical means possible so that these unprecedented looks into the abuses of the Cuban state continue. The Cuban Communist Party will not cede even an inch of power willingly; it never has in 62 years of single-party rule. The only way to drive change in Cuba is via a popular revolt from within alongside economic or even military pressure from without. One hopes that Cubans having the eyes of the world in their pockets for the first time might tilt the balance ever so slightly in their favor.

“Whoever doesn’t have revolutionary genes, or doesn’t have revolutionary blood. Whoever doesn’t have the courage, heart, or brain that adapts itself to the effort and heroism of the revolution. Let them go! We don’t want them! We don’t need them!” Fidel Castro, speech at Mariel, May 1980

Is there anything we can do to help? Are your friends using bitcoin + lightning to raise funds for themselves?

I wonder, should these protests gain traction, if they will fail trigger the imagination and passions of young Americans because they are leftists.