Discover more from The Pull Request

Westward the course of empire takes its way;

The first four Acts already past,

A fifth shall close the Drama with the day;

Time's noblest offspring is the last.-George Berkeley, Bishop of Cloyne

On the campus of my alma mater, the University of California at Berkeley, the northeastern edge of campus is occupied by a rocky outcropping called Founder’s Rock. According to university lore as commemorated in a bronze plaque, it was at this mossy crag that the town’s founders recalled a snatch of poetry whose author gave the nascent town and college their names¹.

Founder’s Rock is situated right by Cory Hall, Berkeley’s electrical engineering building which also houses the Microelectronics Laboratory (in which this Humble Correspondent spent many hours during grad school). It was the first academic laboratory dedicated to integrated circuits shortly after their invention in 1958. Fittingly, the university enshrined the microchip under Cory Hall’s Brutalist eaves. Like a Christ figure ensconced in the crowning niche of a Gothic cathedral, the new Moloch of our age—a stylized shard of patterned silicon connected by cruciform wires—peers over the rock where Berkeley’s founders recited dreamy poetry.

Cory Hall, the electrical engineering building at the University of California at Berkeley, complete with watchful integrated circuit.

Much like Berkeley’s founders, this country has always looked westward for its frontiers, but we West Coasters now sit perched on the limits of the continent. Staring out from the cliffs atop Ocean Beach, we can maybe see the Farallones on a clear day. Other than Hawaii, there’s nothing between us and Asia. The only frontiers left are the ones we invent in order to again conquer.

This magnificent ocean, and the countries that ring it, are now center stage in the greatest struggles of our day: economic, technological, and perhaps one day even military. The trans-Atlantic world that framed the struggles of the 20th century is now a thing of the the past, characters in dramas fit for nostalgic Netflix reboots but not ambitions (or anxieties) of the future.

Lest that sound unjustifiably boastful, let’s take regional stock of ourselves: the most valuable companies in the world—Apple, Microsoft, Facebook, Google, Amazon—are on this side of the continent, crammed roughly between the asphalt ribbon of Highway 5 and the coast. The non-West Coast companies on that list are Alibaba and Tencent, staring at us menacingly from the other side of our pond. The local auto company Tesla is worth several times more than the rest of the US auto sector combined (you’d have to toss in a German or two to even it out). The global conversation that actually matters is happening on Twitter, whether it be Trump going on his latest tear or the Israelis and Iranians threatening each other. Legacy media now is merely an echo and a reaction to Twitter: the Boorstin-ian ‘pseudo-event’ of a press conference has morphed into a Twitter thread. Netflix, based in the upscale hamlet of Los Gatos of all places, is how humanity tells visual stories about itself (itself undermining another West Coast hegemon, Hollywood).

Such a floraison of talent and wealth on one coast is world-historical: the closest parallels that come to mind are 15th-century Northern Italy or 17th-century Amsterdam or 19th-century industrializing Britain. History never quite seems like history when you’re living through it, and yet we are.

Why then must we open the pages of The New York Times to read media anachronisms droning on about West Coast companies they seem incapable of understanding, much less building? Why must our epic stories be told in garish, misleading, but remunerative ways by outsiders, who later turn on the very subjects who made their fortunes in sanctimonious jeremiads that require paragraph-long corrections?

In short, why is our story being told by people whose values are different than ours, whose economic interests conflict with ours, and whose eventual futures are very different than ours?

In the East, everything about your upbringing, tax bracket, and religion may be reliably inferred from which town on Long Island you ‘summered’ in³.

In the East, your every claim to status in a stagnant firmament of prestige is dissected and dog-whistled for public consumption in your Times wedding announcement (should you be so lucky).

In the East, New York and DC elites spend their days busily engaged in rent-seeking, regulatory capture and fighting over the scraps that technology has left behind, while simultaneously ridiculing the very West Coast institutions that have undermined theirs for the past two decades.

In the West, elites make their fortunes in building things (rather than collecting rents), and then rejoice in turning around and funding the nascent startups that challenge the very companies that made them wealthy, just for the goddamned lulz of it.

In the West, you are an individual. Whether your provenance be Boston or Bangalore, your family descended from brahmins or the actual Brahmins, the perceived value of your future arc matters more than your past or parentage.

In the West, hard-fought and daring failure is more noble and marketable than steadfast respectability.

In the West, dropping out of a storied institution to actually create something is more lauded than having graduated from it.

A place, in short, where the past, rentier capitalism, and “that’s just the way it is” trade at a steep discount, and the future, wild-eyed schemes, and “…one more thing” command the highest premiums.

As Frederick Jackson Turner phrased it, in that great reframing of the national story, The Frontier in American History:

[T]o the frontier the American intellect owes its striking characteristics. That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness; that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that masterful grasp of material things, lacking in the artistic but powerful to effect great ends; that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism, working for good and for evil, and withal that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom—these are traits of the frontier.

The true point of view in the history of this nation is not the Atlantic coast, it is the Great West.

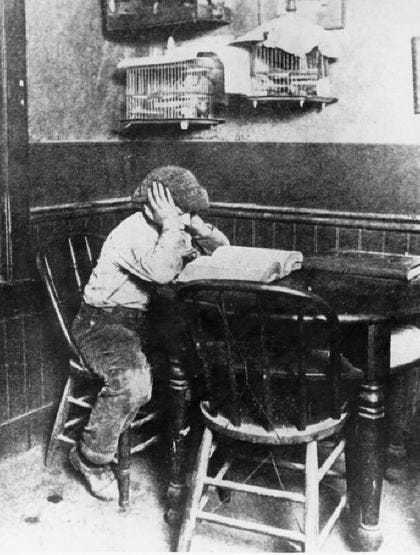

A young Jack London studying at Heinhold’s First and Last Chance Saloon, which still stands in Oakland, complete with original furnishings and slanted floor due to the 1906 earthquake.

The title of this piece is taken from a short story by Oakland native and Berkeley dropout Jack London, perhaps the first West Coast writer to make it big in the mainstream media world of the time. In ‘Make Westing’, a sailing vessel struggles mightily to round Cape Horn on the way to San Francisco (‘westing’ being sailor-speak for gaining longitude westward). Storms are encountered, a sailor falls overboard, a murder ensues, but the hard-driving captain stubbornly continues to ‘make westing’ toward San Francisco.

Such ships were what San Francisco was both literally and metaphorically built on. After surviving the perilous voyage, crews abandoned those East Coast-built vessels for the promise of a new life in the perpetual San Francisco boomtown. The ship owners, unable to find crew, also abandoned the ships on the waterfront. There, they were repurposed as scarce real estate before being physically absorbed by the growing city². The West Coast knows about building on the abandoned wreckage of the East Coast, whether ships or institutions: it’s what we’ve always done.

Gold miners and startup founders followed those first self-marooning sailors, and miner and techie alike either dug for gold or sold shovels to those digging (the latter, such as Leland Stanford, often making out rather better). Recently there’s been another rash of fortune-seeking new arrivals: the shipwrecked writers from East Coast media institutions defenestrated from their once-great perches by the ongoing cold civil war. Substack, like Stanford himself back in the day, is selling them media shovels and they are digging away.

As the The Pull Request hopes to both chronicle and exploit, we’ll soon be living in a decentralized, balkanized jigsaw puzzle of simultaneously interconnected but competing patches of politics, media, and technology. Since this is mostly our doing—politics is downstream of culture, but both are downstream of technology—we West Coasters might as well establish our own media fiefdom on top of our dominant tech one. It’s time to do what we do best, and that’s build better alternatives to the old way of doing things.

For those hesitantly pondering the move to the West Coast, either physical or virtual, consider what Phil Knight recited as his mantra in his memoir Shoe Dog about building a global brand from Portland: the cowards never left and the weak died along the way. As a descendent of the literal pioneers, Knight reminded himself that living at the frontier, whether real or virtual, requires a hardiness of breed absent in many of those who stayed behind. Find the courage to leave the past where it belongs and make westing. The West is waiting, and there’s plenty of frontier to go around.

For those already here, let us take advantage of this pivot point in history and build the New World institutions the future needs while the Old World institutions are as teetering, embattled and confused as they are. To borrow a phrase from Churchill: “until, in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.”

The real story of Berkeley’s founding, as with all local lore, is somewhat more convoluted.

One living museum of this is the Old Ship Saloon on Battery Street, which is built on top of such an abandoned ship. You can tell how much of SF is fill when you consider Battery St., now three blocks in from the bay, used to be the water’s edge.

The weather is so intemperate on the East Coast, they had to verb a season to express the notion of leaving the city to see nature. It’s also another East Coast class shibboleth (cf. ‘aboveground pool’).

Subscribe to The Pull Request

Technology, media, culture, religion and the collisions therein, from your utterly basic Cuban Jewish writer-technologist.

Great piece. I'm very curious about what a new media fiefdom, which somehow suits the underlying shifts in technology and culture, while adhering to values that we presumably hold together, like an attempt at objectivity, would look like.

How is it different than what some big online media have now? Is it supposed to make money? And if so, how? And will its money mechanism give it different incentives than the fiefdoms it attempts to replace?

Frankly, I'm not sure that an op-ed by a screenwriter is the best example of east coast reporting. Editorial pages are famously wacky, and that's kind of the point of their existence, which makes them more similar to social media stars than either side of that analogy would like to admit.

There's a widespread dissatisfaction in tech right now with MSM and with the New York Times in particular. It's understandable, because the NYT is more critical of tech than it used to be (which seems to be part of and in a feedback loop with deeper cultural misgivings), and like other media, we see partisan currents within the paper writing biased stories in the guise of journalism. But that's just part of a larger (and in my opinion, invaluable) institution, that does the hard work of gathering and checking facts everyday.

How would a new media fiefdom do that better, while covering most newsworthy events? Getting to the facts, let alone the truth, is hard, and doing it on a daily basis across many topics is much harder. Doing it in a way that makes money is harder still. I suspect that many people in tech underestimate the difficulty of manuFACTuring, so to speak, the first contact between human understanding and as yet unwritten events.

Once you know what happened, send it as a prompt to GPT-3 and you'll get a great news story written in an inverted pyramid. But GPT-3 doesn't have feet on the ground yet. Those belong to biased humans.